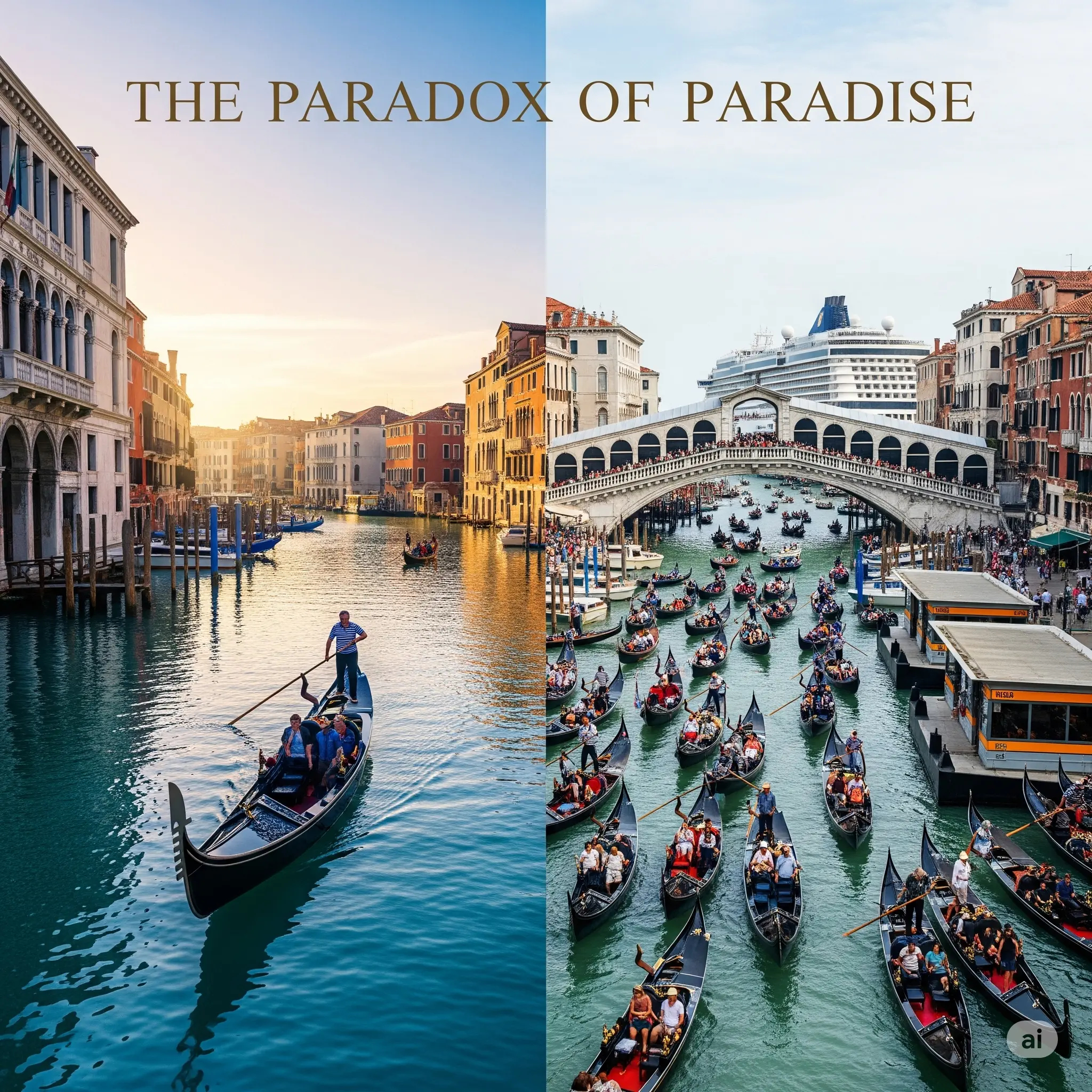

Overtourism is a complex global issue with profound local impacts. To explore it with the depth it deserves, this guide is presented as a multi-part series. We begin by defining the problem and then travel to its most famous victim: Venice.

Defining Overtourism: More Than Just a Crowd

Overtourism is more than just feeling like a place is “too busy.” It is a complex tipping point where a destination’s social, environmental, and physical infrastructure can no longer cope with the sheer volume of visitors.

The Causes: A Perfect Storm

Several global trends have converged over the past two decades to create this perfect storm:

- The Rise of Budget Airlines & the Sharing Economy: Flying has never been cheaper, and platforms like Airbnb have opened up vast amounts of short-term accommodation in residential neighborhoods, often driving up local housing costs and altering the character of communities.

- The “Instagram Effect”: Social media has created a powerful visual checklist for travel. Millions of people are now driven to capture the exact same iconic photo (the Trevi Fountain, the view from a specific cliff in Santorini), which concentrates an enormous number of people into a few very small, specific “hotspots.”

- The Cruise Ship Phenomenon: A single mega-cruise ship can disgorge 5,000+ passengers into a small, historic port city for just a few hours. This creates a massive, temporary surge that overwhelms local infrastructure without contributing significantly to the overnight economy (as passengers eat and sleep on the ship).

- A Growing Global Middle Class: More people around the world have the disposable income and desire to travel than ever before in human history.

Case Study 1: Venice, Italy – The Sinking City Loved to Death

There is no better symbol for the crisis of overtourism than Venice. A city of impossible beauty, a UNESCO World Heritage site, it is a miracle of engineering and art. It is also a city under siege, not from an invading army, but from the very people who come to admire it.

The Symptoms of a City Under Siege

Before the pandemic temporarily cleared its canals, Venice was welcoming up to 30 million visitors a year. For a fragile, historic city with a resident population of only around 50,000, the impact has been devastating.

- Demographic Collapse: The number of full-time Venetian residents has plummeted. They are being priced out of their own city by the conversion of long-term rental apartments into lucrative short-term tourist lets. The city is in danger of becoming a hollow, living museum with no authentic community left.

- Infrastructural Damage: The wake from massive cruise ships and countless water taxis was eroding the foundations of the historic buildings and polluting the delicate lagoon ecosystem. The sheer foot traffic of millions of people wears down ancient stone bridges and pathways.

- Loss of Authenticity: Basic shops needed by residents—bakeries, hardware stores, local grocers—are being replaced by an endless monoculture of souvenir shops, gelato stands, and tourist-trap restaurants.

The Innovations and Controversies: Venice’s Fight for Survival

Venice has become a global laboratory for solutions to overtourism. These measures are often controversial but represent a desperate and innovative attempt to save the city from itself.

The Cruise Ship Ban

After years of protests and warnings from UNESCO, the Italian government in 2021 passed a decree to permanently ban large cruise ships from entering Venice’s historic center and the fragile Giudecca Canal. The ships are now required to dock at a mainland industrial port, a hugely significant and hard-won victory for the preservation of the city.

The Tourist Entry Fee and Reservation System

This is one of the most-watched anti-overtourism experiments in the world. Starting in 2024, Venice began phasing in a system that requires day-trippers (visitors not staying overnight in the city) to book their visit in advance and pay an entry fee (around €5) on peak days.

- The Goal: The primary goal is not to generate revenue, but to manage visitor flows. By setting a cap on the number of day-trippers, the city hopes to ease the intense crowding on the busiest days.

- The Impact: This is a revolutionary step. It fundamentally changes the idea of a city from a completely open public space to a managed resource, much like a national park or a museum. The world is watching to see if this model can work and if it will be adopted by other overwhelmed destinations.

Promoting “Detourism”

The city’s tourism board and local initiatives are now actively trying to encourage “detourism.” This involves creating guides and promoting itineraries that take visitors away from the hyper-congested St. Mark’s Square-Rialto Bridge axis and into the quieter, more authentic residential neighborhoods like Cannaregio or Castello. They are encouraging visitors to explore the other islands in the lagoon, such as the colorful fishing island of Burano or the glass-making island of Murano, to disperse the crowds and showcase the region’s wider attractions.

Venice’s struggle is a poignant and critical lesson for the future of travel. It is a fight to find the delicate balance between a welcoming, open city and a livable, sustainable one.

Case Study 2: Barcelona, Spain – When Tourism Ignites a Social Backlash

For years, Barcelona was a global tourism success story. The 1992 Olympics showcased it to the world, and visitors flocked to its Gaudí architecture, Gothic Quarter, and vibrant beach culture. But for many of its residents, the success has curdled into a nightmare, leading to a powerful social backlash and the rise of a term that has gone global: turismofobia (tourist-phobia).

The Symptoms of “Turismofobia”

The grievances of Barcelona’s residents are a textbook example of the social costs of overtourism.

- The Housing Crisis: The explosion of unregulated, short-term tourist rentals (like Airbnb) in central neighborhoods caused rental prices to skyrocket, forcing long-term residents, especially the young and the elderly, out of their communities. This process of gentrificación turística (tourist gentrification) has hollowed out the social fabric of historic areas.

- Overwhelmed Infrastructure: Public spaces and services are stretched to their breaking point. Locals find it impossible to navigate the crowded alleys of the Gothic Quarter, get a seat on the bus, or even do their daily shopping at markets like La Boqueria, which have become more of a tourist attraction than a functional market for residents.

- Loss of Quality of Life: The rise of rowdy “party tourism,” with endless bar crawls and disruptive behavior, has made life unbearable in neighborhoods like Barceloneta. This has led to widespread and visible frustration, with protest movements and graffiti like “Tourist Go Home” becoming common sights.

The Innovations and Regulations: Barcelona’s Pushback

In response, Barcelona’s city government has become a global pioneer in implementing aggressive regulations to reclaim the city.

- Crackdown on Unlicensed Rentals: The city has waged a multi-year war on illegal tourist apartments, imposing massive fines on platforms like Airbnb and HomeAway for listing unlicensed properties. They created a public website where anyone can check if a rental listing is legal, empowering residents to report illegal activity.

- Limiting New Hotels: The government placed a moratorium on the construction of new hotels and tourist accommodations in the hyper-congested city center.

- Managing Hotspots: Access to the famous “monumental zone” of Park Güell is no longer free. It now requires a timed, pre-booked ticket, a measure designed to dramatically reduce the number of people in the park at any one time and ease congestion.

Case Study 3: Maya Bay, Thailand – A Paradise Loved to Death, and Reborn

If Barcelona is a story of social fallout, Maya Bay is a stark lesson in ecological collapse. Located on the uninhabited island of Koh Phi Phi Leh, this stunningly beautiful cove, with its sheer limestone cliffs and emerald water, was made world-famous by the 2000 film The Beach.

The Tsunami of Tourists

After the film’s release, Maya Bay became a non-negotiable stop on the Thailand tourist trail. At its peak, the tiny cove was receiving up to 6,000 visitors and 200 speedboats per day. The consequences were catastrophic.

- Ecological Destruction: Speedboats anchored directly on the fragile coral reef, smashing it to pieces. Sunscreen from thousands of swimmers polluted the water. The constant noise and activity drove away all native wildlife, and scientists estimated that over 90% of the bay’s coral had been destroyed. The paradise was dead.

The Drastic Solution and Miraculous Rebirth

In a bold and unprecedented move, the Thai government made a drastic decision in June 2018: they indefinitely closed Maya Bay to all tourists. The plan was to give nature a chance to heal. The results were astounding and occurred faster than anyone predicted. With the pressure of tourism removed, the remaining coral began to regenerate. And, most remarkably, dozens of native blacktip reef sharks, which had been absent for years, returned to use the shallow, protected bay as a nursery.

The Reopening: A New Model for Sustainable Access

After nearly four years, Maya Bay reopened in early 2022, but under a completely new and strict set of rules.

- No Boats in the Bay: Boats are now completely banned from entering the bay itself. They must dock at a new, purpose-built pier on the other side of the island.

- Strict Visitor Caps: Only a limited number of visitors are allowed per hour, and visits are capped at one hour.

- No Swimming: To protect the regenerating coral and the juvenile sharks, swimming in the bay is no longer permitted. Visitors can only wade up to their knees.

Maya Bay has become a globally significant, living experiment. It is a powerful, hopeful story that proves that even a severely damaged ecosystem can recover if given a chance, and it provides a potential blueprint for how to manage fragile natural sites sustainably.

Case Study 4: Kyoto, Japan – Protecting a Culture of Serenity

The challenge in Kyoto is not social collapse or ecological destruction, but a more subtle and complex friction: the clash between modern tourist behavior and a deeply ingrained culture that prizes order, serenity, and etiquette.

The Symptoms of “Kanko Kogai” (Tourism Pollution)

In Japan, the term for overtourism is Kanko Kogai (tourism pollution). In Kyoto, a city of serene Zen gardens, historic temples, and the elusive world of geishas, the symptoms are unique.

- The “Geisha Paparazzi”: The most acute problem is in the historic Gion district. Tourists, desperate for a photo, would often mob, chase, and even touch the geishas (geiko) and their apprentices (maiko), treating them like theme park characters rather than professional artists going to their appointments.

- Disrespect and Disruption: Incidents of tourists trespassing into private gardens, ignoring signs, and disrupting the quiet, contemplative atmosphere of sacred temples became widespread.

- Overwhelmed Public Services: Buses became so packed with tourists that local residents, especially the elderly, found it difficult to go about their daily lives.

The Gentle Pushback: Innovations in Etiquette and Technology

The response in Kyoto has been quintessentially Japanese: less about aggressive confrontation and more about education, management, and the gentle enforcement of social harmony.

- Etiquette Campaigns: The city has launched extensive campaigns to educate visitors. This includes multilingual pamphlets, apps, and signs in Gion that clearly state the rules, such as “Do not touch the geishas” and “No photography on private streets,” with fines for non-compliance.

- Technological Solutions: The city’s tourism board has developed real-time crowd-monitoring websites and apps. Before heading to a famous temple like Kiyomizu-dera, a tourist can check the app to see the current congestion level, allowing them to choose a less crowded time or an alternative destination.

Kyoto’s struggle is a fascinating case study in how a destination can fight to preserve not just its buildings, but its intangible culture of serenity and respect in the face of overwhelming global attention.

The Solution Isn’t to Stop Traveling, It’s to Travel Better

Becoming a more responsible traveler doesn’t require radical sacrifice. It requires a shift in perspective and a series of small, thoughtful choices that, when multiplied by millions of people, can create transformative change. Here are the core principles.

Read Also: Discover top destinations for sailboat charters worldwide

Principle 1: Disperse – Go Beyond the Hotspots

Overtourism is often a problem of concentration, not just of numbers. Millions of visitors flock to the same 1% of a destination. The single most effective thing we can do is to spread out.

- Explore Second Cities and Neighborhoods: Instead of joining the crowds in Venice, consider the incredible art of nearby Padua or the charming canals of Treviso. Instead of fighting through Barcelona’s Gothic Quarter, spend an afternoon in the bohemian, village-like neighborhood of Gràcia. Every major city has fascinating, less-touristed districts that offer a more authentic glimpse into local life.

- Embrace the “Micro-Adventure”: Redefine what constitutes a worthy travel experience. Find joy not just in the world-famous monument, but in a quiet local park, a bustling neighborhood market, or a conversation with a local shopkeeper.

Principle 2: Re-Time – Travel in the Off-Season

Traveling during the “shoulder seasons” (the months just before and after peak season) or the off-season is a powerful tool.

- The Benefits: You will be met with fewer crowds, lower prices on flights and accommodation, and a more relaxed atmosphere. Destinations are often more beautiful in the autumn light or the crisp air of early spring. More importantly, you provide a welcome economic boost to local businesses during their slower periods, creating a more stable, year-round tourism economy.

Principle 3: Go Deeper, Not Wider – Stay Longer

Resist the temptation of the “10 cities in 10 days” itinerary. Rushing from one hotspot to the next is a major contributor to overtourism, as it treats places like checklist items.

- The Power of Staying Put: By choosing to stay in one place for five days or a week instead of just one or two, you transform from a “tourist” into a “temporary resident.” You have time to move beyond the main square, discover local cafes, build a rapport with the owner of the corner bakery, and contribute more meaningfully to the local economy.

Principle 4: Support Local – Follow the Money

Where you spend your money has a direct and profound impact.

- Choose Local Accommodations: Whenever possible, opt for a locally owned boutique hotel, a family-run guesthouse (pension), or a legally registered and taxed apartment rental, rather than a massive, foreign-owned hotel chain where a large portion of the profits may leave the country.

- Eat and Shop Locally: Seek out neighborhood restaurants, not the ones with multi-language menus on the main square. Buy your souvenirs from local artisans, not from generic tourist shops selling mass-produced trinkets. Your spending can be a powerful vote for the preservation of local culture and community.

Principle 5: Respect – Be a Gracious Guest

As the case of Kyoto showed, sometimes the greatest impact is not economic or environmental, but social. Being a good traveler is about being a good guest.

- Learn a Few Words: A simple “Hello,” “Please,” and “Thank You” in the local language goes a long way.

- Dress Appropriately: Be mindful of local customs, especially when visiting religious sites.

- Ask Before You Photograph: People are not tourist attractions. Always ask for permission before taking a close-up photograph of a person.

- Be Aware of Your Footprint: Be mindful of noise levels in residential areas, respect private property, and follow local rules and etiquette.

The Future of Travel: Innovations Shaping a Better Path

The good news is that the industry is adapting, with new models and technologies emerging to create a more sustainable future.

- The Rise of “Slow Travel”: This growing movement is the philosophical antidote to overtourism. It champions a slower, more immersive form of travel that prioritizes connection to local people, culture, and food over the frantic ticking off of a bucket list.

- Technology as a Tool for Good: As we saw in Kyoto, technology can be a powerful ally. Crowd-monitoring apps that guide tourists to less congested areas, platforms that connect travelers with authentic local experiences, and tools that make it easier to find and support sustainable businesses are all part of the solution.

- Regenerative Tourism: Leaving a Place Better Than You Found It This is the cutting edge of sustainable thought. The idea is to move beyond “sustainability” (which aims for a neutral impact or causing no harm) to “regeneration” (which aims to have a positive, restorative impact).

- What does it look like? It can mean choosing a tour operator that invests a portion of its profits in local community development projects. It can mean staying at a hotel that is actively involved in reforestation or coral reef restoration. It can even mean dedicating a small part of your trip to a local volunteer activity, like a beach cleanup.

A Traveler’s Pledge: The Final Word

We began this journey by confronting the Paradox of Paradise—the reality that our collective love for the world’s most beautiful places can be a destructive force. We have seen how this paradox has pushed cities like Venice to the brink, scarred landscapes like Maya Bay, and frayed the social fabric of places like Barcelona and Kyoto.

But we have also seen hope. We have seen innovation, resilience, and a growing global awareness that we must change course. The future of travel is not in question, but its form is. The old model of high-volume, low-impact (economically) and high-impact (socially and environmentally) tourism is unsustainable.

The power to shape a better future rests, in large part, with us, the travelers. Every trip we take is a series of choices. By choosing to disperse, to travel in the off-season, to stay longer, to support local businesses, and to act as gracious guests, we cast a vote for the kind of world we want to explore.

Travel is a privilege, and with that privilege comes responsibility. Let us be a generation of travelers known not for the crowds we created, but for the connections we made and the respect we showed. Let us be explorers who leave a place not just as we found it, but a little better, ensuring that the paradox of paradise can, at last, be solved, and that these incredible destinations can be treasured for all the generations to come.